IDENTITY CRISIS: Naked mole-rats aren’t moles, or rats. They’re more closely related to guinea pigs.

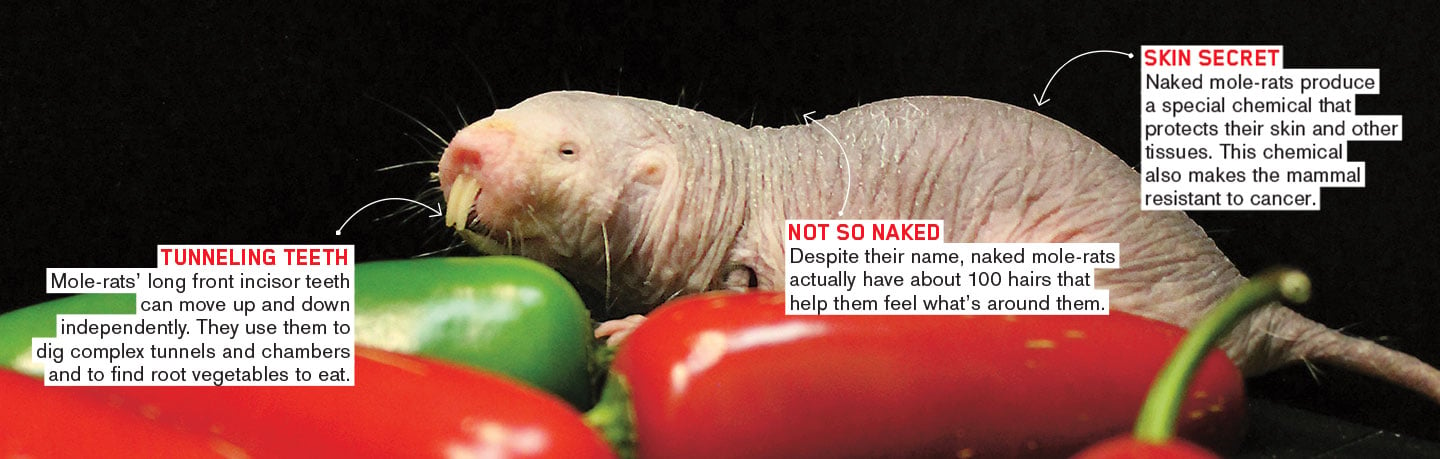

This weird-looking creature is a naked mole-rat . . . and it’s probably not hard to see how it got its name. These nearly hairless rodents live together in burrows beneath the deserts of east Africa. It gets hot and uncomfortable inside these cramped underground holes. But the naked mole-rats have a way to beat the heat: They’re nearly immune to pain caused by high temperatures.

For most animals, “Pain is primarily protective,” says Gary Lewin, a neuroscientist at the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in Berlin, Germany. The sensation of pain is like an alarm warning organisms to stop doing something harmful—like touching a hot stove. Without this signal, they could badly injure themselves. About 20 million years ago, naked mole-rats branched off from other mole-rat species and lost this pain response—making life a little more manageable in their sweltering burrows.

This weird-looking creature is a naked mole-rat. It’s probably not hard to see how it got its name. These rodents are almost hairless. They live together in burrows under the deserts of east Africa. It gets hot and uncomfortable in these cramped underground holes. But the naked mole-rats have a way to beat the heat. They’re nearly immune to pain caused by high temperatures.

For most animals, “pain is primarily protective,” says Gary Lewin. He’s a neuroscientist at the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in Berlin, Germany. The feeling of pain is like an alarm. It warns creatures to stop doing something harmful—like touching a hot stove. Without this signal, they could badly hurt themselves. About 20 million years ago, naked mole-rats branched off from other mole-rat species. They lost this protective pain response. That makes life a little easier in their sweltering burrows.