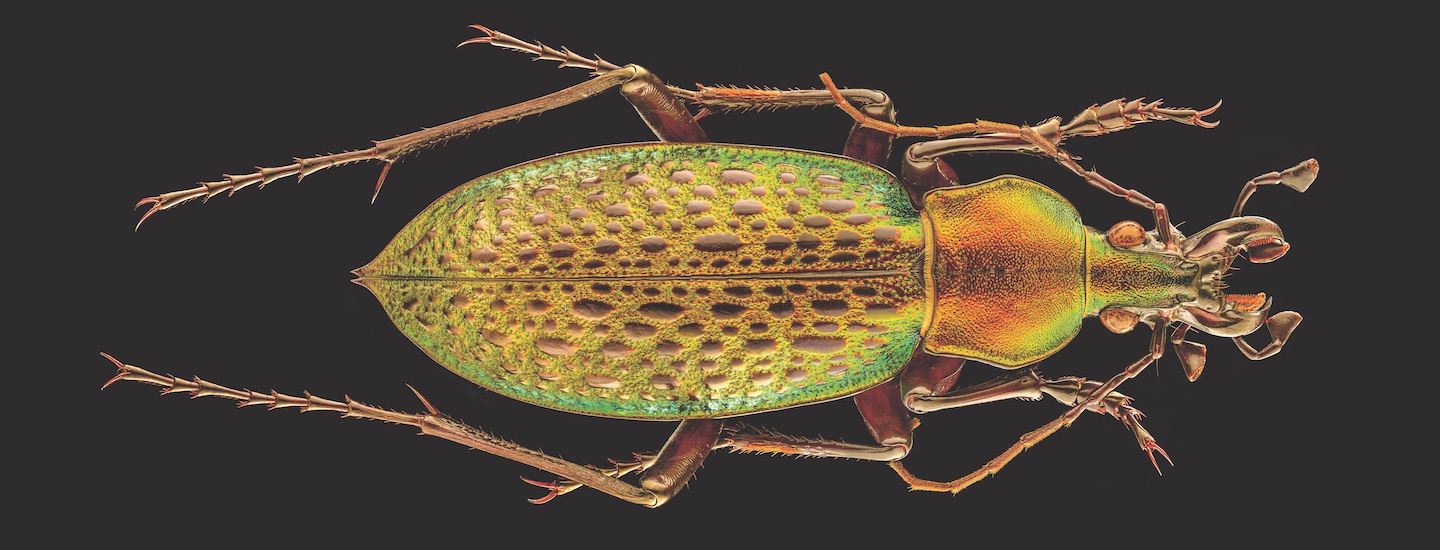

Most of the time, Levon Biss can be found snapping photos of world-famous athletes or movie stars for international advertising campaigns. But recently he’s been focusing his camera on a completely different type of subject: insects.

At the one-of-a-kind studio he designed at his home in London, England, Biss has attached a microscope lens to a camera to capture magnified photos of insects. Because each photo has such high resolution—the sharpness of an image—he can print enormous detailed shots of the tiny creatures. Some of his photos stand 3 meters (10 feet) tall—as tall as a one-story building.