When a new pigment like YInMn is made (see the article New Blue in the 11/21/16 issue of Science World), conservation scientist Narayan Khandekar snaps up a sample. He adds it to the pigment collection he oversees at the Harvard Art Museums in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

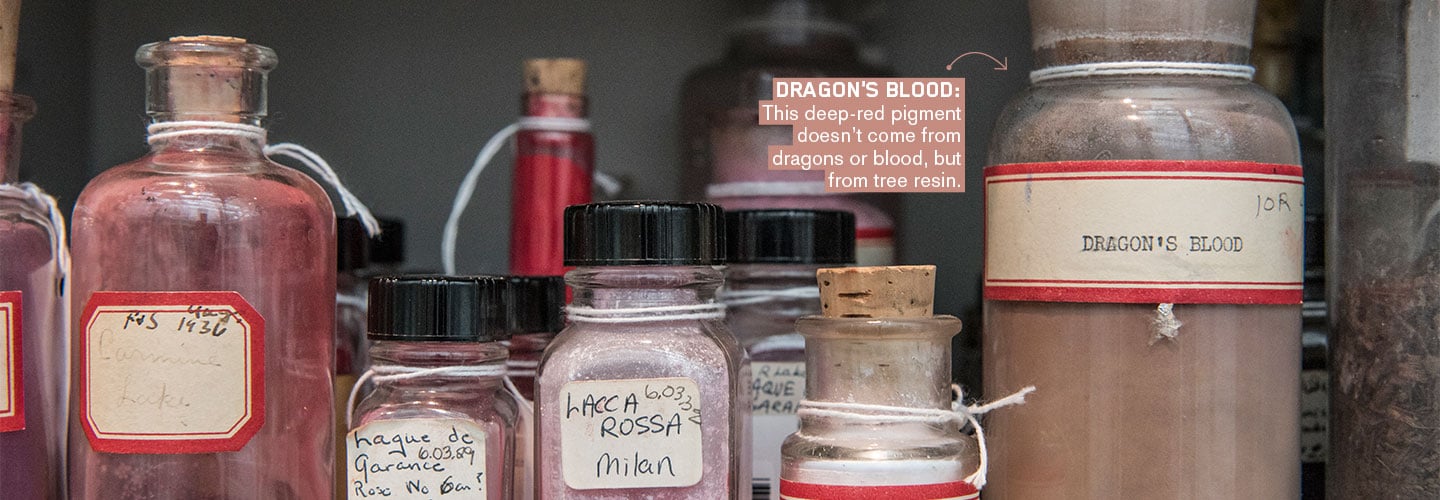

Pigments are substances that absorb and reflect different wavelengths, or colors, of light. They can occur naturally in minerals or plants, or they can be created in a lab—as YInMn was. Throughout history, people have chosen pigments for their bright or unique colors. The pigment collection at the Harvard Art Museums, which was started in the 1900s, now holds about 2,500 samples from around the world.