Last spring, passengers on Hawaiian Airlines received something in addition to their in-flight snacks: sunscreen. Attendants passed out samples to encourage tourists visiting the islands to use types of sunscreen that are safer for corals. Scientists have found that chemicals in some sunscreens currently on the market harm reefs, and the airline hoped to inform people about the problem. Now Hawaii has joined several seaside spots around the world in banning sunscreens that contain these ingredients.

Last spring, passengers on Hawaiian Airlines got something besides their in-flight snacks. Attendants passed out samples of sunscreen. They wanted visitors to the islands to use types of sunscreen that are safer for corals. Scientists have found a problem with some sunscreens on the market. Chemicals in them harm reefs, and the airline hoped to let people know. Several seaside spots around the world have banned sunscreens that contain these chemicals. Now Hawaii has joined them.

BABY CORAL: Corals release eggs and sperm into the water. When a sperm meets an egg, a coral larva forms. The larva attaches to the seafloor and grows into a coral polyp.

BABY CORAL: Corals release eggs and sperm into the water. When a sperm meets an egg, a coral larva forms. The larva attaches to the seafloor and grows into a coral polyp. GROWING UP: The polyp builds a hard, cup-shaped skeleton under itself. As the coral grows, it adds material to its home.

GROWING UP: The polyp builds a hard, cup-shaped skeleton under itself. As the coral grows, it adds material to its home. TINY BUILDERS: Young corals build homes on top of other corals to create reefs—a process that can take up to 10,000 years. Each polyp gets most of its energy from algae called zooxanthellae living within its tissues.

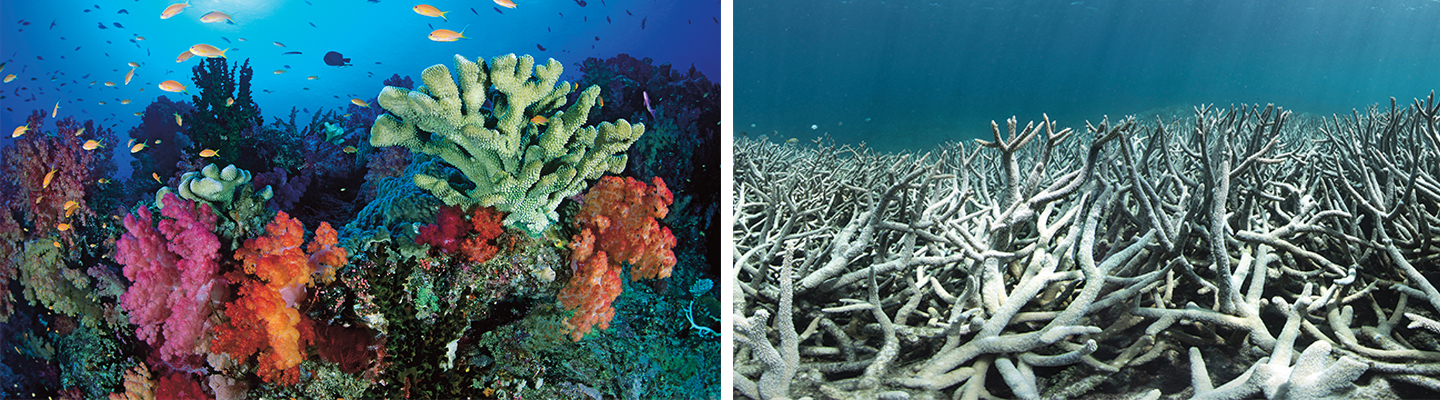

TINY BUILDERS: Young corals build homes on top of other corals to create reefs—a process that can take up to 10,000 years. Each polyp gets most of its energy from algae called zooxanthellae living within its tissues. STRESSED OUT: Stress from things like pollution can cause coral to lose their algae. Their skeletons turn white as a result, a process known as bleaching. If the stress continues long term, the corals can die.

STRESSED OUT: Stress from things like pollution can cause coral to lose their algae. Their skeletons turn white as a result, a process known as bleaching. If the stress continues long term, the corals can die.