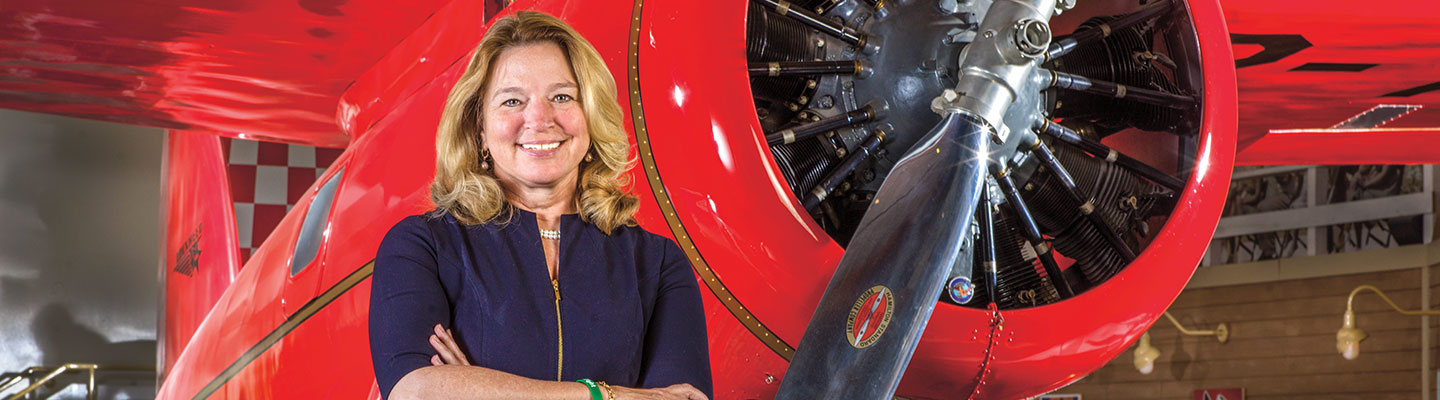

Ellen Stofan has long been fascinated by rocks—and not just those on our planet. She’s studied the geology of Earth, Venus, Mars, and Titan, one of Saturn’s moons. Stofan spent more than 25 years working as a planetary scientist for organizations like U.S. space agency NASA. As chief scientist, she held NASA’s most senior science position. Now, Stofan is taking on a new leadership role as the first female director of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

The National Air and Space Museum, located on the National Mall, is the most visited museum in the United States. More than 7 million people a year come to check out its one-of-a-kind exhibits. They include everything from some of the first airplanes ever to take flight to artifacts from historic moon landings. The museum first opened its doors in 1976. After four decades in operation, it needed a renovation. Stofan spoke with Science World about her career and overseeing the museum’s redesign, which she hopes will inspire future generations of scientists.