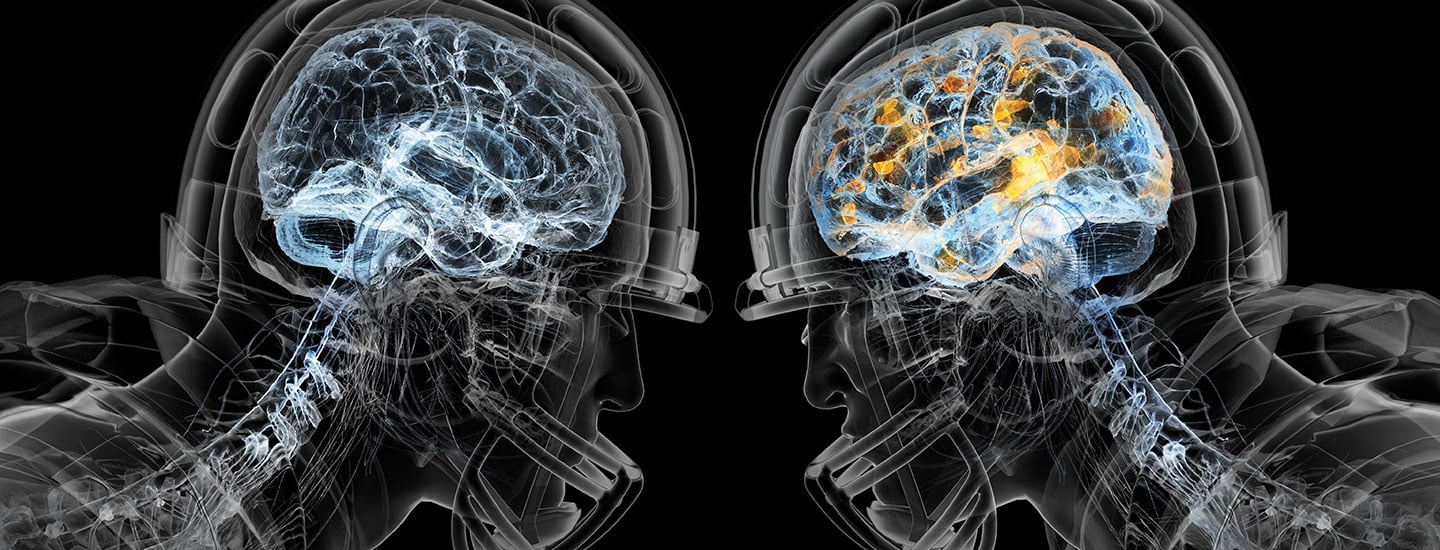

BRAIN TEAM: Stern (left) and McKee

On February 4, millions of Americans will tune in to watch the Super Bowl. Two of those viewers will be Robert Stern and Ann McKee. They’re not just any football fans, though. Stern and McKee are neuroscientists at Boston University in Massachusetts who study the brain. They’ve been investigating the effects of football on players’ brains.

Recently, Stern was part of a team of scientists, led by McKee, who conducted the largest study yet of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). This disease affects athletes with a history of repeated blows to the head. It’s marked by brain damage that worsens over time, continuing long after players retire. Stern spoke to Science World about their research and how young athletes can protect themselves.